Inaki Williams always knew his brother Nico was special, even if his younger sibling used to get so nervous he would ask Inaki, already a star in Bilbao, not to watch his youth games at the Athletic Club academy.

Inaki is a pioneer.

He helped raise Nico while their parents worked tirelessly to make ends meet, but also paved the way for his brother and other sons of immigrants to represent a club whose policy of only fielding players born or raised in the Basque Country inevitably meant the squad has historically reflected the predominantly white society around it.

Inaki, 29, was not the first player of African heritage to represent the club - that was Jonas Ramalho, son of an Angolan father and Basque mother, in 2011 - but he is the first black player to establish himself at San Mames, having made more than 300 La Liga appearances, including an unprecedented 251 in a row.

Nico, eight years his junior, is, in Inaki's words, now "making waves in football" too, and any nerves the youngster feels these days are channelled into realising childhood dreams of performing on the biggest stage alongside his big brother, mentor and guardian.

"As an older brother, it makes me really proud to see how he has grown, to see how he is improving as a footballer. He has no ceiling," Inaki tells BBC Sport. "I'm here to help him, to teach him and give him everything he needs."

It is a journey that began long ago, and a long way from Bilbao. Their mother, Maria, was pregnant with Inaki when she left Ghana with father Felix in search of a better life.

The couple crossed part of the Sahara barefoot. Inaki only learned the full extent of their story when he was 20. He had known his father had problems with the soles of his feet, but not that scorching sand was the reason why.

Felix and Maria made it to the Spanish territory of Melilla in north Africa, jumping a border fence, but were detained by the civil guard.

A lawyer advised them to lie, to say they were from war-torn Liberia instead and seek political asylum.

He arranged help in Bilbao from Catholic priest Inaki Mardones, who met the couple at Abando railway station when Maria was seven months pregnant, found them an apartment and took them to hospital for Inaki's birth.

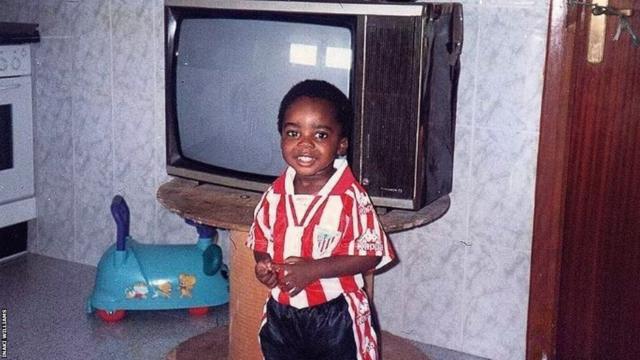

Mardones baptised the future star, even gave him his first football shirt, and became his godfather.

He is whom Inaki takes his name from.

Critics call it xenophobic or racist. Some cite the case of Miguel Jones, a Bilbao native born in Equatorial Guinea who trained with the club. Policy at the time, however, dictated players must be born locally, so Jones was let go and instead enjoyed a successful career at Atletico Madrid in the 1960s.

Jones himself dismissed claims of racism, citing white players who experienced the same fate, and celebrated Inaki's emergence before his death in 2020. Perhaps more poignant than a trophy, then, will be the Williams brothers' legacy.

"It has been very rewarding to see how Athletic has evolved across time," says Gaizka Atxa, the Mexico-born founder of a fans' group named after Fred Pentland, a legendary former English coach of the club.

"Athletic is a reflection of our society here and seeing the Williams brothers flourish means that any immigrant or son of immigrants has a decent opportunity to play for our club.

"That just opens wide possibilities as to what Athletic could become in the next few decades."

How long they will continue to flourish together is a topic of debate. Nico, who wears 'Williams Jr' on his back, is highly sought-after, notably from Chelsea, where his father once tore tickets.

The 21-year-old's individual goal against Atletico in December was one of six he has scored in 29 games for Athletic this season. He is also joint second in La Liga's assist standings.

"Inaki is helping Nico a lot in everything," says sporting director Gonzalez. "Nico is a very good player, but he is very young and you can imagine a lot of noise around him with clubs, with agents. But Inaki is the best example of hard work."

Athletic fans can reluctantly accept when a star player goes as long as they leave money - in the form of a fat transfer fee - on the table. Aymeric Laporte, a £57m departure to Manchester City, for example. Nico's previous contract was due to expire in June 2024, but in December he signed an extension through to 2027, under his brother's guidance.

"Inaki, of course, was also in on these decisions with his family," says Gonzalez. "They feel very well here in Bilbao. They believe in the project. They are very happy with the team, with the coach, with everything. They also have the love of the supporters.

"For sure, at another club Nico could have gone for free to a Champions League club, earning much more money or winning more titles. But in this moment he has the feeling he has to continue here and Inaki is a very important person for him to take the best decisions in his professional career."

In any case, Nico and Inaki have unfinished business in Bilbao, a cup final to win - for the fans, for the city, for the club, for Felix and Maria.

©BBC